Jacques Torres is an accidental yogi. I’m not sure he would agree with this and I, for one, certainly did not expect to talk about yoga when I sat down with him at his chocolate store in Tribeca. Frankly, I’m not sure what I expected. Jacques, like many creative geniuses or successful business owners (in his case, both), is hard to pin down, and so I came prepared to be unprepared. While his attention appears to dart in a million directions, he is completely present, processing inspiration and connecting the dots between life and work at an impossible pace. He spots opportunities to share his passion with others, engaging with customers and showering them with chocolate. His generosity is inspiring. As I listened to him talk about his life as an artisan and his passion for creating, I realized that I was, as I had anticipated, caught completely off guard. I came to interview him and instead, he was teaching me about yoga.

15 Feb 2013

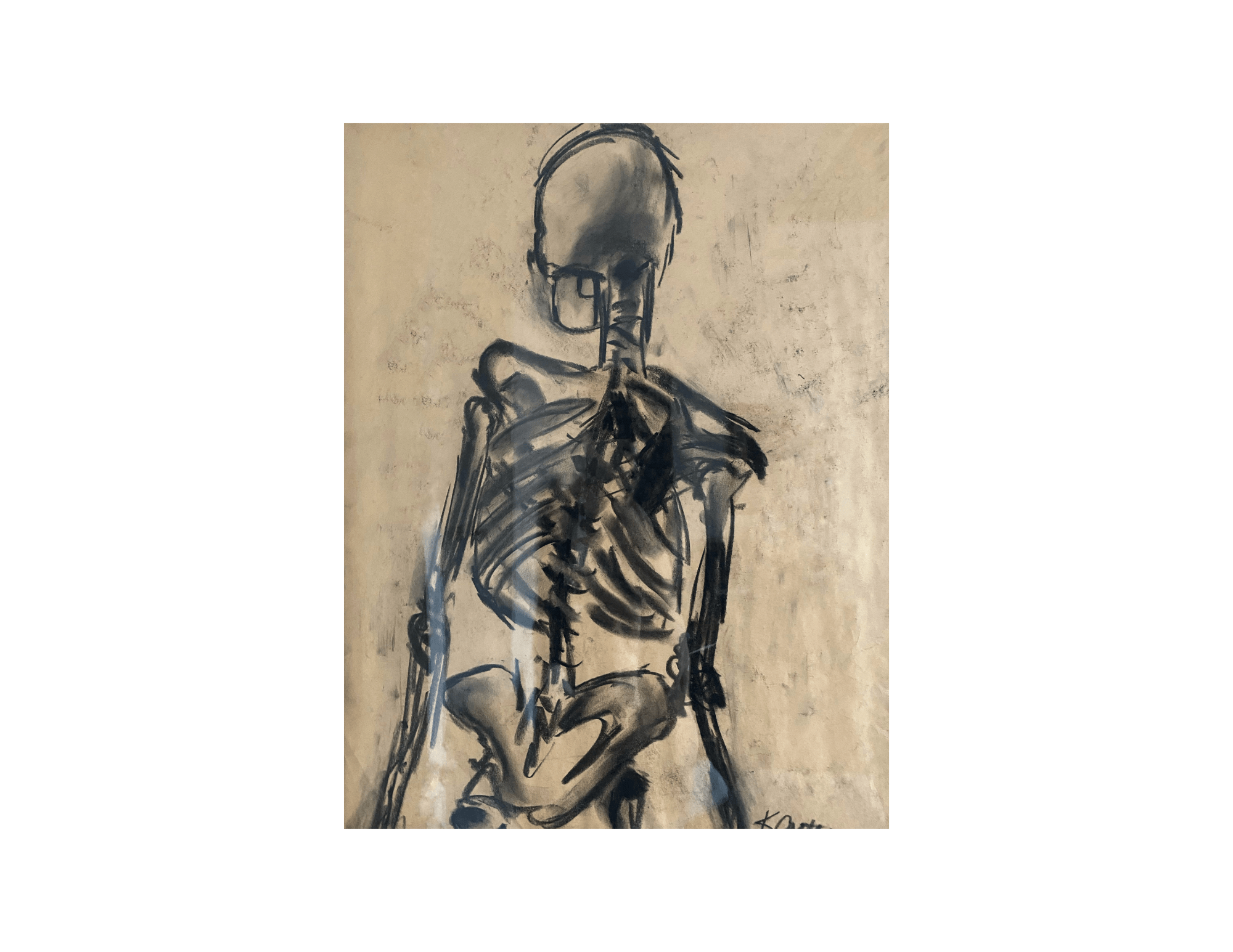

Jacques Torres

Jacques’s story is inspiring. Born into a humble family in a small town in southern France, he had no specific desire to be a chef. “I wanted to be a craftsman. My father was a carpenter. My brother is a chef. My other brother is a carpenter. We all work with our hands. Yes, I am a chef. Yes, I work with food, but mostly I work with my hands and I create. I am a craftsman.” One testament to the artisanal connection between cooking and carpentry: Jacques and his brother did all of the woodwork in his first store in DUMBO, Brooklyn. “The medium can be food, the medium can be wood, the medium can be plaster . . . whatever it is, we are craftsmen. As a craftsman you spend all your life, every hour of the day, devoted to your passion. Money is not the goal. The goal is the way you’re going to live. My first goal was to spend time in the kitchen. To make things. To make people happy.”

His dedication to his craft was recognized in 1986, when Jacques received the prestigious Meilleur Ouvrier de France, an award honoring tradesmen in various fields. At 26, he was the youngest chef to be granted this distinction. His talents eventually brought him to Le Cirque, where he held the title of Executive Pastry Chef for eleven years. “I don’t believe in talent,” he says. “I don’t think I’m talented. I think that I work very hard. For me, talent doesn’t exist; you have to train all your life.” In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali explains that practice (abyhasa) and a detachment from the results (vairagya) are tools to still the mind. The three qualifications of practice—that it be attended to for an indefinite period of time, without break, and with one’s whole heart—are the pillars of Jacques’s philosophy. “If I peel an apple with you, I’m going to peel it in a third of the time as you. Your eyes are going to look at my hands and right away you’re going to know how to do it, meaning your brain learns extremely fast. But your hands and your body do not learn fast. You have to really work on it, and work on it, and work on it. Years of experience will help you do it. I am not a craftsman from eight until five—I am always working.”

I asked Jacques how he stays inspired and I felt instantly connected to his response. “Passion is going to make you think about your craft. Thinking about your craft is going to help you innovate and stay inspired. I’m walking down the street and I see the maple trees and those beautiful colors and I think, oh my God, I need to do something with those leaves or with maple syrup. It’s in the air. You have to think about those things constantly. Constantly.” He then told me a great story about being struck by inspiration while eating fortune cookies at a Chinese restaurant. He called up a company that makes fortune cookies and asked if they could put his phrases inside, and then he ordered cases of fortune cookies and dipped them in chocolate. The messages reveal Jacques’s mischievous nature: “Difference between men and chocolate? Chocolate gives you pleasure every time!” Delivered with a twinkle in his eyes, his message behind the message is to have fun, and this is one of the things that I love about Jacques—he is like a little kid in his own candy store.

His point about inspiration was not lost on me; my own teaching is inspired by my life. When I’m feeling like my well is dry, it’s because I’m either trying too hard or walking through my life with my eyes closed. To use Jacques’s words, “Who sits at a desk and says, ‘I will have an idea’? You just have to love what you do and know that inspiration can come from anything, anywhere, and anyone. You have to have an open mind.” I asked him who he considered to be his biggest teacher, expecting to hear about his relationships with famous chefs. “Life is my teacher,” he said. “Going through life, you have to be aware. You have to be aware of your surroundings—of other people—and I think you learn everyday.”

For me, my passion for yoga fueled my desire to teach, and so I wanted to know if the same was true for Jacques, who is a dean at the International Culinary Center in New York. “I don’t think every craftsman likes to teach. I think it’s a question of education or personality. Education because when I was trained, the person who helped me didn’t want any recognition but told me that I had to help other people. So a man came to me and asked me for my help, and I thought about it and I said, ‘Yes, of course I will help you.’ And then he asked if I wanted equity in his business—one percent or two percent—and I said, no. ‘Why should I take equity in your business? But . . . against the equity I don’t take, you better help other people. If I hear that someone asked for your help and you don’t help them, I will never help you again.’ I think that’s craftsmanship.” Offer freely to others without expecting anything in return. Help others because you love what you do so much that you can’t imagine not helping them. This is a true teacher.

But teaching can be so hard—it can lift you up or bleed you dry—and I find it especially challenging because teaching is my craft. I asked Jacques what he felt was the hardest part of teaching and I’m still chewing on his answer. “I don’t know the hardest part. I know the best part. The best part is to see the student succeeding. The hardest part, I don’t know. You teach because you love to do it. And then it’s the choice of the students to keep going and succeed.” Wow (moment of silence). This is the biggest lesson I took away from our conversation; I want my students to care so much because I care so much—about yoga, teaching, their success—and if they choose not to take on the work, I take it personally. I can’t disconnect from teaching because teaching is my medium. Jacques struck right at the heart of the work I’m trying to take on: letting go.

When you live and breathe your craft, when your life is about creating for the pleasure of others, burnout is inevitable. I was happy to hear that, even for Jacques, the art of balance is a practice. “I refuse to work on Sunday or Monday morning. I really have to have something very important to do to work on those days. I need those days for me. I will go on my boat and do things for me. I refuse to sleep less than eight hours. I know I cannot function well if I don’t rest.” But was he always this disciplined? “There was a time when I worked too much and I got myself into trouble, physically. I suffered through it and then I learned, OK, I have to structure my life in a way that I’m going to get the rest I need. If you don’t put gas in your car, it doesn’t work.” Amen. People who know Jacques know where to find him when he’s not at work. “Fishing is one of those things that helps me relax. It’s going to get me out of my head. Even when I come back exhausted, because it’s very tiring, at least my mind gets a break. I have the same challenges every day. When I go fishing I don’t have those same challenges. I come back to work and I can think a little bit more clearly.”

Jacques’s business has expanded exponentially since the opening of his first shop in Brooklyn. He now has shops in Tribeca, Rockefeller Center, Chelsea Market, and the Upper West Side. I wanted to know what drives his growth. “The growth of the company is almost happening on its own. It’s almost like I’m in the backseat and I’m just trying to keep up. Sometimes I push to get a store to open, but then it just happens. I don’t feel 100 percent responsible. Things happen.” Jacques is clear about what he wants and he works hard to achieve his goals, but there is an element of faith in his business strategy—a belief that the results will come—and he has the wisdom to know when to surrender. He offers me an example. “I’m thinking we need more space to produce. I decide I’m going to buy a building somewhere outside the city. Someone comes to me and says, you’re not going to buy, you’re going to rent the space we have.” He told me that at every turn, he was offered an answer to every foreseeable obstacle. “I looked for something and it fell in my lap. I don’t know how to explain it . . . positive energy? I go with the flow. I have fun doing it. Sometimes, I’m in my shop late at night or early in the morning, when no one is around, and I think to myself, ‘How the hell did this all happen?’ ”

As our time together came to an end, I tried to convince him that he was a yogi, explaining (in one short sentence) the entire gist behind the philosophy of yoga. He seemed intrigued but unconvinced, assuming (as most people do) that the only way to be a yogi is to bend your body into ridiculous shapes. But his response only confirmed what I already knew, which is that Jacques is more of a yogi then most yogis I know. “If you’re not present—if you’re not there—the customers can feel it. I think that’s the key to success.” I couldn’t agree more. Our conversation ended and Jacques dashed about his store in a fury, still managing to stop and talk to customers and, lucky for me, bestowing on me more goodies than I could possibly consume (although I somehow managed). Our conversation has stayed with me and as I digest his wisdom, it continues to reveal hidden layers of meaning and unexpected opportunities for application in my life and work. Jacque makes chocolate for the sake of making chocolate, for the love of making chocolate, and for the joy of sharing his creations with others. Merci, Mr. Chocolate. Tu es vraiment un yogi extraordinaire.

Photos by Melina Hammer.

This interview was a pleasure to read. What an inspriation to witness such a passion for what you do that it drives every part of your life in a positive spiral. He sure sounds like a yogi to me too. 🙂